Why Use Digital Archives in Social Studies?

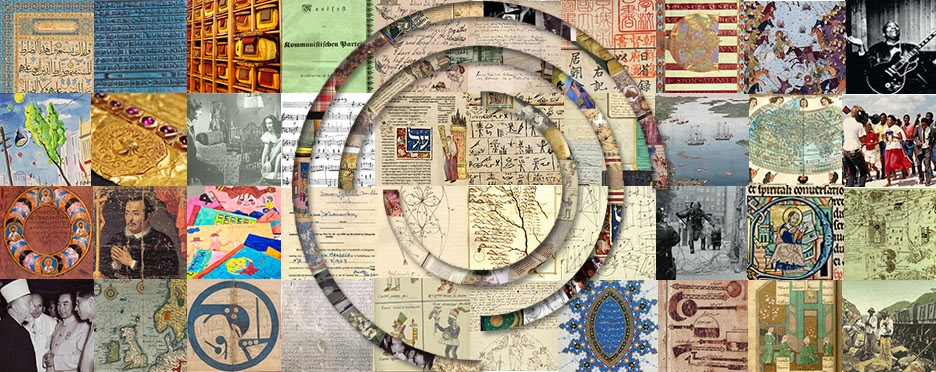

Before we answer the question of why use digital archives (DA) in social studies, we first need to define what DAs are and what they are not. In history, we are no longer tied only to the “check the record” type of research wherein we load up the old microfiche and while away the hours as newsprint bleeds into our retinas. Now, we also have methods that allow us instantaneous access to historical information from the comfort of our own homes. Now, hours of computer screen time burn our retinas senseless. As technology evolves towards the future, our methods for saving the past expand. Well, not exactly save it – it’s already long gone. We continue to try to capture some of the more important elements of what has gone before us for the purposes of posterity.

Before we answer the question of why use digital archives (DA) in social studies, we first need to define what DAs are and what they are not. In history, we are no longer tied only to the “check the record” type of research wherein we load up the old microfiche and while away the hours as newsprint bleeds into our retinas. Now, we also have methods that allow us instantaneous access to historical information from the comfort of our own homes. Now, hours of computer screen time burn our retinas senseless. As technology evolves towards the future, our methods for saving the past expand. Well, not exactly save it – it’s already long gone. We continue to try to capture some of the more important elements of what has gone before us for the purposes of posterity.

Moving on quickly from that stale-dated joke. We can actually look at archives from two different vantage points in time to gain a better idea of the process. From today’s perspective looking forward, whether on a personal level or from a societal vantage point, we can make some educated guesses as to what would best represent or say the most about ourselves or society sometime into the distant future. Again, from today’s perspective, however this time looking back at a particular time and place, we are afforded that looking-lens by way of the archival record. Obviously, the further you go back the potential for greater inaccuracies increases. Also, we tend to lose important elements of those records, or only have disparate pieces to puzzle together our understanding of that particular past or at least a perspective on that past. As we venture down this archival path together we will see that many more considerations come into the mix in the art and science of archiving the historical record.

For the purposes of posterity we hope today’s standard of record-keeping does its job well in encapsulating the import of what took place yesterday. Please don’t think too hard on that last one — it hurt just as much to write it as it does to read it.

Let’s take a step back for a moment from the digital side of things, and ask ourselves first what are archives? Well, let’s lead with the International Council on Archives. They should have a pretty good idea on what makes for a good archival record.

For archives to be of value to society they must be a trusted resource. To achieve this they must have the following qualities:

- Authenticity – the record is what it claims to be, created at the time documented, and by the person that the document claims to be created by.

- Reliability – they are accurately representing the event, although it will be through the view of the person or organisation creating that document.

- Integrity – the content is sufficient to give a coherent picture. Sadly not all archives are complete

- Usability – the archive must be in an accessible location and usable condition. Earthquakes, hurricanes and war, for example, can all render archives useless.

As one can only imagine much goes into the crafting of an archive, and of course what qualifies as archival material for the historical record. Acknowledging that there are many variables that archiving considers, the following should lead teacher and student alike down a good path when it comes to doing sleuthing of their own.

Archives have several characteristics:

- They are only retained if they are considered to be of long-term historical value. This can be difficult to assess but what it means is that archive collections do not and cannot hold every document ever created.

- They are not created consciously as a historical record. Their strength is that they are a contemporaneous record and must be viewed in the light of who drew up that document and why.

- Documents do not have to be ‘old’ to be an archive, just no longer required for the use for which they were created.

- They come in a wide range of analogic and digital media – not just paper documents. Archives encompass written documents, electronic resources (including websites and email), photographs and film, and sound recordings.

Perhaps providing us with an apt juxtaposition to those caretakers of another kind (ironically enough as those tasked with the purging for a society that over produces and wastes much), colloquially speaking, we could consider archivists as the “custodians of society’s memory”. Humourously, another irony that comes to mind is that when blogging about and inquiring on this topic of digital archives one can become quite amazed at the wealth and depth of knowledge that exists on this wonderful world wide web of ours. But then, that last word ‘ours’ that’s a bit of a misnomer really, as it’s only ours because of our ability to access it, and put there by the people that own it. Not so fast you say. Well, for the purpose of this blog we won’t go down the road of who owns what on the internet. Suffice it to say, a lot of control and power goes into the creating and ownership of digital archival records, but similar to archives themselves, public access is the goal and objective of most reputable and legitimate organizations.

Back to that irony piece. I hope, perhaps somewhat like an archivist, it is the gems that one finds while looking for something else that makes appealing this sleuthing about the internet.In this case searching for documents and records that bring the archival historical record to light and the process itself, a resulting worthwhile endeavour.

Here, then, are a couple of those gems:

Before getting too deep into the ins and outs of digital archives, we must acknowledge some of the principles and dynamics underlying archival science. Who records history, and how they do it, has historical, political, and social consequences. Bias is systemic in archival science — archives have traditionally been created and kept by oppressive bodies and institutions. The digitization of records can certainly recreate oppressive repositories that marginalize particular voices and stories.

Digitization of existing archives and the creation of brand new digital archives, though, helps to address these issues to encourage more inclusive history writing. The fact that we can access so many digital archives democratizes the ability of teachers to teach with primary sources and the ability of our students to learn how to “do” history (Mason Bolick, 2006). Archival research is no longer just the domain of scholars and university researchers. Further, the digital sphere offers the opportunity for marginalized peoples to preserve, contextualize, and share their histories as well as the opportunity for people to collaboratively contribute to digital collections and digital histories.

Answering why we should use digital archives in social studies becomes easier when one realizes how many archival records already exist online. Therefore, educating the high school history learner becomes less about teaching them how to search out obscure or difficult-to-find records, and more about ensuring students have the requisite tools to navigate content online and cultivate students’ analytical skills. Differentiating between primary and secondary resources themselves would seem a much easier process. However, depending on which angle is being pursued along with the context of one’s research influences whether a source might be considered primary or secondary. Still, primary sources in and of themselves are worth their weight in gold for any worthwhile historian seeking to piece together fabrics of time lost to tell yesterday’s stories today. Within those parameters digital archivism has been afforded the scope to select from a wide expanse of sources especially as our digital era seems able to hold the unlimited ability to introduce new means and collections of works to those online spaces.

We aim to be a service and a resource primarily for teachers, though with the appropriate direction and level of support, a helpful tool for students as well. The primary goal is to provide up-to-date access to those indispensable documents of the historical record. Of a secondary regard, but by no means less important consideration is that by saving teachers valuable prep time, an effectively set-up resource allows for efficiency and ease-of-use navigation, to help build students’ knowledge and engage them with research that interests them, while avoiding the pitfalls of frightfully free-falling through internet rabbit holes.

Through this process of first asking ourselves why digitize archival records and then how best to accomplish such a noble goal, we began to unravel what the hosting or the collating of a narrowly focused or a more generally-scoped historical record would entail. Could such an inquiry in fact perform both those endeavours simultaneously? Besides possibly providing some bemusement to the more discombobulated of you presently perplexed and pleasant enough readers (that is because you are actually still indeed reading this sentence), I hope that you can humour me as I give pause even in this present moment to my own thinking and place in this sentence, much like how our project only just slowly evolved to becoming realized more as a preview and purview of what already exists out there, in as far as it concerned the digitalizing of the historical record. We were, after all indeed, not to design and carve out a one-stop resource exhausting all types of research inquiries, with no need to navigate beyond our cobbled-together archival record of all things considered historically significant, or at least what we deemed important? Okay, full confession, much hyperbole certainly abounds in that last statement, but truth be told, an idea that took much time to germinate needed time to sprout out its weeds before it’s more burgeoning buds could appear. More questions would arise, especially with the accumulation of a surfeit of records arriving in our inbox, as well copiously attaining many more, now canvassing the internet with an eye more finely attuned to the task at hand. However, alas, in the end we would indeed become tied and bound, albeit I offer up a juxtaposing of James Joyce’s more joyful meaning as found in Ulysses; a clock winding down for our purposes forebodes our forced conclusion by those very same bounds of time.

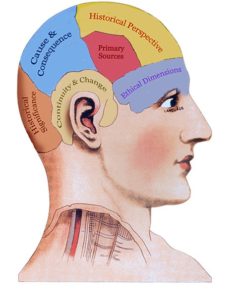

Moving on quickly from that last monstrosity of a barely sensical thought sequence, we will endeavour to inform the reader how the topic and actual skill of learning about digital archives relates to those purest of paired pursuits — teaching and learning. Quite simply, our goal as prospective teachers should be to encourage and inspire our students to think critically, and as I happened across The Historical Thinking Project I quickly grasped that this graphic, even if just existing as a fantastical representation of the human mind, is way more effective at revealing how “historical thinking and literacy” relates to students demonstrating knowledge. In every way possible we want to stretch our students thinking by introducing them to new content, concepts, and ideas, whether as primary or secondary sources, that help support original findings but probably more importantly challenges and contests those arguments, all while practicing these new-found skills of analyses, in the exercising of their critical thinking (brain) muscles.c

The developers of this concept and resource broke down these skills for the burgeoning scholar – an historical thinker – into the following 6 criteria:

The developers of this concept and resource broke down these skills for the burgeoning scholar – an historical thinker – into the following 6 criteria:

- Establish historical significance

- Use primary source evidence

- Identify continuity and change

- Analyze cause and consequence

- Take historical perspectives, and

- Understand the ethical dimension of historical interpretations.

The Historical Thinking Project was directed by Professor Peter Seixas, at the University of British Columbia, and coordinated by Jill Colyer, an educator with 20 years experience with the Waterloo Region District School Board in Ontario and OISE (University of Toronto). As a non-profit educational initiative, it was funded by the Department of Canadian Heritage (Canadian Studies Program) and THEN/HiER.

Many of these intangibles are applicable to today’s teachers guiding students’ quests to gain knowledge themselves and to properly contextualize, assess relevance, and determine what can be learned from the past. However, as must always be noted when accessing and assessing the historical record, the voices and perspectives collected have predominantly been those purporting the narrative of the majority, more often nullifying the voices of the forgotten. As archivist Dominique Luster (2018) declares, “history [recording is more often] a series of strategically curated choices that can uplift some or erase others, based on the decisions by those with the power to curate.” Producing a more complete and just historical record requires archivists “develop better practices that contribute to racially-conscious and culturally-competent archival theory.” Originally heard as a TED Talk in Pittsburgh, PA, her impassioned message, Archives Have the Power to Boost Marginalized Voices, (2018) was to give voice to the voices she describes as “purposely oppressed, suppressed, or buried from history.

Examining as we should from outside the dominant narrative, we need to investigate and correct the historical record, that even if it no longer ignores the oppressed voice, it too often has spoken for and about that forgotten perspective. Considering an Indigenous Peoples perspective requires their historians to educate from within. As Ellen Cushman instructs with her piece, “Wampum, Sequoyan, and Story: Decolonizing the Digital Archive,” concerning digital archives, “scholars need to understand the troubled and troubling roots of archives if they’re to understand the instrumental, historical, and cultural significance of the pieces therein.”

Further contextualizing our inquiry pursuit to our collective interests within this teaching program, I’d like to jump off of colleagues Ryan and Alex’s inquiry into digital storytelling as a form of teaching or more specifically engaging learners in the “doing of learning”, and draw in Cushman’s concern questioning “how well any archival holding of a story or digital story can create the situation of storytelling: the listening, holding on to, picking up, and letting go, based on the types of relationships between people who together make ‘artifacts’ meaningful.” I’m therefore left with two overriding feelings, that understanding, as in understanding the failings of the past along with the failings of how the past was recorded and for whom, is key; and, that relationship building and meaning making through the respectful use of artifacts and what they reveal, must underlie all the work we do to understand the past’s significance in paving more equitable and holistic futures.

So, we’ve now discussed some of the importance for why digitized archives matter, along with how the unearthing of archival records benefits the social studies student’s research capabilities. Next, we want to tackle how best to integrate archival records whatever the type or purpose . . . but first, let’s discuss some ways to teach primary sources!

Teaching Primary Sources

Many, many, many resources are out there to help teachers teach the use of primary sources in their social studies classrooms. But before we examine the different exemplars available online, or even self-created examples, we should break down some of the processes and what real benefits accrue from engaging in the practice of archival research. Like other aspects of “doing history” much of the satisfaction comes from establishing a stronger connection to the material you are looking at. To gauge an archive’s significance you want to try to understand that piece or document within its context and what it meant then and to the people it affected, along with how and why it impacts on today. A more difficult task is to unearth details about who or what organization did the original archiving, and how that manifested itself through the following: biases of the archivist or the organization (much like how a newspaper through its editors and owners would hold a bias); external influences, both positive and negative, whether that be governments or corporations etc.; blind spots, namely those perspectives or voices that went unheard; and lastly, but not exhaustively as far as considerations; limitations on how that work was performed. All told, performing the task of primary source evaluation could seem overwhelming for the high school student. That is why our intention was to tailor our approach to teachers, providing them with both a tool set and a pared-down perspective on how best to engage students in learning this crucial skill.

Across our courses within the Secondary PDPP we have encountered many new ways to create a dynamic teaching and learning experience, seen beneficial for both ourselves and future students. For our EDCI 352 Multiliteracies Across the Curriculum, we designed lesson plans with these ideas in mind, and fortunate for this tech inquiry our group created a unit plan on a historical fictional novel, Obasan, which provided a personal and archival account of Japanese Canadians’ internment experience during WWII. A few of the documents included here reveal how a primary source analysis can be introduced in a variety of ways, all while being thought-provoking, reflective and reflexive, and imaginably, relevant to today’s students.

Primary Source Analysis Tools:

Here are a few other places to help you get started:

- Teaching and Learning with Primary Sources

- Engaging Students with Primary Sources (for teachers on engaging students with primary sources and using primary sources in inquiry-based learning:

Historica Canada, which actually has a great list of 10 tools for working with primary sources in Canadian history classrooms, has an excellent lesson plan (created collaboratively by educators across Canada) on introducing your students to working with primary evidence.

Some videos you can use in the classroom as teaching tools to help students understand primary (and secondary) sources:

How to integrate digital archives

There are many reasons why social studies teachers may be hesitant to use digital archival sources, or any archival primary sources, in their classrooms. These may include (Sandwell, 2008):

- Lack of experience: Not all social studies teachers have a history background, so many simply don’t have the personal experience that would make them feel comfortable navigating and parsing through historical primary sources themselves, let alone teaching their students how to do so. Even many teachers with history backgrounds will be uncomfortable with diving into archival sources.

- Lack of time: Sifting through archives — especially if they are organized or indexed poorly, if they are simply not user-friendly in other ways, or if you don’t know exactly what you’re looking for — can take up a large chunk of time. This can mean a lot more prep for teachers and a lot of time in class for students dedicated to searching. This can take away from covering other curricular content and competencies.

- Curricular concerns: This concern is essentially a blending of the first two. If a teacher is unsure about how to use primary sources in a way that connects to their course content, knowledge, and skills, this can take up valuable time needed for other parts of the curriculum.

- Student knowledge: Some teachers fear that primary sources in generally may not be accessible or comprehensible to students.

Historian and history education expert Ruth Sandwell (2008) offers 4 ways to help address these concerns and effectively integrate primary documents into high school history lessons:

- Illustrate more than one curricular theme, issue, or event: Ask yourself and your students what “big ideas” a particular source or set of sources illustrates, or what learning outcomes it can be used to achieve.

- Use primary documents to add value to existing resources: Do not expect to teach using just primary sources — find other content or resources first that the primary sources will enhance. There are two ways to do this:

- To enhance content knowledge — Add value to class/teaching resources by exemplifying, extending, or even contradicting key facts or ideas (i.e. present material and extend or problematize it with primary documents).

- To engage students — Primary sources can be used to draw students into a topic by presenting an immediate and often dramatic perspective on a topic, particularly if the source is something meaningful to them.

- Make the text and context accessible to students — Before launching into primary source analysis or use by students, teach them how to understand and evaluate historical context and how to interpret primary sources (see resources in above section). Make sure sources add to students’ existing knowledge and skills while they build new ones (Battershill & Ross, 2017).

- Invite critical thinking, not just recitation of facts — Prompt students to go beyond what they can superficially detect, and don’t connect documents to “correct” answers or interpretations.

Sandwell’s list is addressed to the use of primary sources more generally. To make it more relevant to using sources specifically from digital archives, I would add the following point:

Use digital archives that have connected educational materials or further resources, such as museum-archive sites. Things on these sites such as digital exhibitions, books, podcasts, or other content associated with and/or created from the organization’s archival material provide that content anchor Sandwell suggests. This should make it easier to then find and use/relate relevant archival material to support or extend that anchor. Some places may also have lesson plans and other useful resources for navigating and integrating the archive’s material available specifically for teachers.

Some general ideas for learning activities using digital archives

- Digital archive scavenger hunts: The Ohio Historical Records Advisory Board provides an example of how to conduct one of these with your students including activity note-taking templates that will help students not only conduct the research but think metacognitively about the process. This type of activity is helpful for acclimatizing students to finding and analyzing primary sources.

- Digital escape rooms: This is essentially a way to further gamify the scavenger hunt activity — students find the required items which are “clues” they need to escape! It might be a good follow up to a more in-depth scavenger hunt, perhaps as a formative assessment!

- Family trees/Family history: This is good for making history personally relevant to students and many archives include documents relevant to genealogy (e.g. birth and death certificates), such as the BC Archives’ Genealogy Collection.

- Create your own digital archive

- Contributing to collaborative digital history projects, such as HistoryPin or projects found on Zooniverse.

- Creating digital exhibitions: This can be a very engaging activity that teaches students not only how to research but also how to curate what they’ve found and narrate history.

- Digital storytelling: Tools such as Twine can be used for this (see below).

- Creating virtual tours: This type of activity can help students learn the importance of space and place in history and encourage them to anchor stories to specific places, which can really help history come to life.

- Timelines: A mainstay of many high school social studies classrooms. You can have your students attach digital primary sources to their timelines to illustrate key dates, people, and events. Composing a linear timeline using only or primarily primary sources may be a good way to help students practice historical narrative composition using primary sources. Students could look to this Age of Revolution timeline as an example.

- Mysteries/Investigations: You can provide students with a case and a list of sources to find (similar to the scavenger hunt) and ask them to try to solve an historical mystery of some kind. This can be time consuming, so there are activities like this online already that were created using digital archival sources (see Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History below). See Historical Scene Investigation to find examples that might be enough inspiration to create your own!

- Blogging: Short blogs can be used as an analysis assignment. Have students find a resource that is interesting to them and write a blog post which includes a visual of or link to the source with their analysis of it.

- Creating documentaries: Turn your students into documentarians by asking them to curate and collate sources into a short documentary with voiceover — this will help with their analytical, narrative, and video editing skills.

All of these suggestions are inherently exploratory, constructive, speculative, and inventive — and this is the distinct advantage that integrating digital archives/collections into classroom learning offers (Battershill & Ross, 2017). Digital archives offer students a greater ability to explore the world from the comfort of their own seats while critically and creatively constructing their knowledge from the new information and experiences they encounter in those archives.

Specific examples of resources

Local/British Columbia: Twine story — Chinese Immigration to Canada (by Emily McCue)

National: Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History

Great Unsolved Mysteries of Canadian History offers ready-to-go historical learning activities that have digital primary sources built in. Each mystery essentially has its own mini, multimedia archive attached — sources curated and collected digitally for each specific historical issue/mystery (Sandwell & Lutz, 2014). It is a “series of instructional websites based on the premise that students can be drawn into Canadian history and archival research through the enticement of solving historical cold crimes. All the material is provided free as a public service” (Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History, “About”). It provides support for teachers that helps not just with the mysteries but with historical teaching in generaly and has a Mystery Quest site with mysteries indexed by age group:

in addition to the series of mysteries found on their main site:

Indigenous: Sq’éwlets – A Stó:lō-Coast Salish Community in the Fraser River Valley

This is not an “archive,” but it is a digital collection of primary materials curated and shared by the Sq’éwlets nation to preserve their language and history. This introductory video, found on their website (linked above) explains what the site and sources are for. The sources shared, including audio from nation members, are not sources that would be found in a traditional archive — such as audio and pictures of material culture — but which are absolutely invaluable and necessary for accessing the history and experiences of the Sq’éwlets nation and recognizing the legitimacy of non-textual primary sources in general.

Such digital spaces, which are different from traditional archives but which can no doubt be seen as archives in the digital age, not only democratize research, but also helps to decolonized archives and archival science in general. Such archival websites from Indigenous communities are arguably more useful than many traditional archives as they provide the voice of those being documented while hosting preserved materials (material culture, stories, and language itself) in a place that puts those materials into or next to the social context which created them, keeping the materials’ relationship with the community that produced them intact (Cushman, 2013).

International: Centropa

Further Archives/Resources

The following lists are meant as a place to get started and are by no means comprehensive. Many municipalities, provinces, countries, museums, libraries, universities, corporations, First Nations, and other institutions have extensive collections that are available digitally.

British Columbia:

- Jewish Museum & Archives of BC

- BC Archives

- Colonial Despatches of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, 1846-1871

- Victoria Fire Insurance Plans

- Victoria Police Department Charge Books

- British Colonist

Canada:

- CBC Digital Archives – For Teachers

- Canadian Parliamentary Historical Resources

- Library and Archives Canada

- The Arquives – Canada’s LGBTQ2+ Archives

- Mackenzie King Diaries

Indigenous:

UBC has compiled an excellent list of digital Indigenous collections. Content relating to the lives of Indigenous people can also be found throughout many of Canada’s, the provinces’, and many other archives. Keep in mind the colonial context in which such materials were usually created and in which they are generally maintained as well as how such archives frame and treat Indigenous experiences and voices.

International:

- Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives

- Centropa

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- US National Archives

- The Newberry – Digital Collections for the Classroom

- Digital Library of the Middle East

- African History Digital Document Portal

- Southeast Asia Digital Library

- UK National Archives

- United Nations Digital Library

Academic References

Battershill, C. & Ross, S. (2017). Using digital humanities in the classroom: A practical introduction for teachers, lecturers, and students. Bloomsbury Academic.

Cushman, E. (2013). Wampum, Sequoyan, and Story: Decolonizing the digital archive. College English, 76(2), 115-135.

Mason Bolick, C. (2006). Digital archives: Democratizing the doing of history. International Journal of Social Education, 21(1), 122-134. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ782136.

Sandwell, R. (2008). Using primary sources in social studies and history. In R. Case & P. Clark (Eds.), The Anthology of Social Studies: Secondary Education (pp.295-307). Pacific Educational.

Sandwell. R. & Lutz, J. (2014). What has mystery got to do with it? In K. Kee (Ed.), Pastplay: Teaching and learning history with technology (pp. 23-42). University of Michigan Press. DOI: 10.1353/book.29517.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.