Is a Lack of Imagination Bad?

An interesting thing that I’ve noticed about myself is that I do not have a particularly vivid visual imagination. I never have. I didn’t pay much attention to this over the years because it was never important. When we were discussing memory improvement techniques in educational psychology this week, however, I was forced to think quite a bit about my unexciting visual imagination because a large proportion of the host of simple memory improvement techniques revolve around attaching words or concepts either to images or together as composite images in our brains.

The idea of attempting many of these makes my brain hurt. For me, the idea of coming up with a set of images for to memorize lists or commit to memory each new concept I learn sounds like a very time-consuming process for someone like me.

I think it’s because of my less-than-cinematic visual imagination that I tend to excel with and prefer to work with the written word. It also makes the idea of utilizing external visual images to learn and teach somewhat intimidating for me. I have discovered, however, that I can be more effective when working with these external images than I thought and my ability to communicate with images, particularly craft narratives using images, is better than my ability to conjure images in my brain and externalize them. When I see visual content, I am capable of organizing it into coherent narratives or ideas. I don’t think in visual stories, but that doesn’t prevent me from communicating with them. Stemming from my own experience with a less-than-robust visual imagination, I am very curious about how this spectra of visual imagination affects learners across it. We might, for instance, be tempted to think that blindness might limit a learner to auditory input only or that sighted people have the same abilities to think in visuals and receive and communicate visual information.

Aphantasia

I once worked with a girl who was completely incapable of forming visual images in her head. This is called aphantasia, something I have decided I must have a mild form of. She was an accomplished musical theatre performer capable of rendering visual the imagination of the playwright and director. As this reveals, and as Anna Clemens states in a very fine Scientific American article titled “When the Mind’s Eye is Blind,” aphantasia does not affect creativity – the brain has ways to compensate for this lack of imagination.

The Brain and Creating Visuals

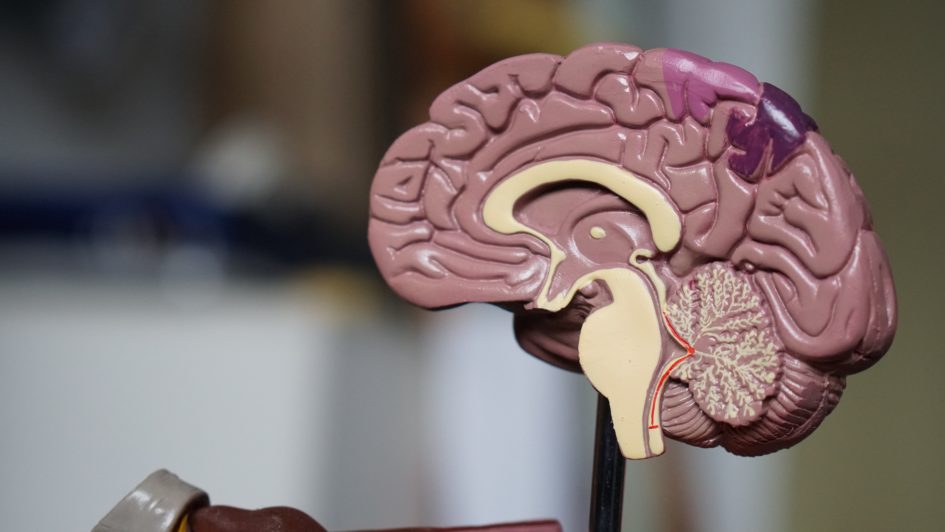

I am immensely interested in medical history and I once read a book called The Tale of the Dueling Neurosurgeons: The History of the Human Brain as Revealed by True Stories of Trauma, Madness, and Recovery. It uses interesting case studies from history to teach about the structure and functions of the brain. The book discusses a phenomenon many of us are probably familiar with: face blindness. Those who are face blind cannot remember people’s faces because of either congenital or acquired damage to the fusiform gyrus, the part of the brain responsible for responding to faces. Another case study discussed how blind people ARE STILL CAPABLE OF SEEING FACES. This occurs, scientists hypothesize, because face recognition has been so crucial to human evolution that, when the fusiform gyrus is undamaged, other sensory information, such as sound can be translated into visual images because brains with no visual input will rewire themselves to accept non-visual sensory input as visual. Our senses do nothing but provide the brain with information that it then processes:

Blindness and Sightedness – Separate?

Special equipment needs to be used for such facial recognition through sound, but it is well-documented that blind subjects are capable of using a kind of echolocation to form visual images of the world around them. See the Invisibilia episode “Batman” about Daniel Kish, a man who is not just blind but has no eyes, who developed this type of echolocation skill. It does a much better and more thorough job of explaining this phenomenon than me.

Neuroscientific research such as this, as well as that on phenomena such as synesthesia, really helps to emphasize the connectedness of senses and, therefore, media. As an extension, it helps to really drive the point for me that we artificially separate our senses and their contribution to our learning. Moreover, we limit ourselves based on faulty information about how our senses work. If blind people can see through sound, why can we not learn using all of our senses? How does this support or complicate dual code theory?

Expectations

The Invisibilia episode also discusses psychologist Bob Rosenthal’s research on how people’s abilities can actually be affected not only by their perceptions of themselves, as my non-alphabetic narrative skills were by my perception that I’m not a visual person, but also by other people’s expectations of them. This obviously has implications for teaching children. Our personal thoughts that lie just in our brain can affect our students. Out of Rosenthal’s research came the idea of the Pygmalion Effect – expecting intelligence or success out of students can increase their performance, while expecting poor performance can lead to that poor performance; this occurs because we engage with students differently based on our expectations of them.

If we have high expectations of and belief in our students (and ourselves) when it comes to inter- and crossmodal learning, will they be more likely to succeed in this learning, or at least in approaching it? How can we creatively teach in a way that allows atypical learners of many types, or just people across (for example) this spectrum of visual imagination, to learn in cross- and multi-modal ways when they can’t access the same materials? For example, the visual aspect of YouTube videos likely won’t be accessible to students who are visually impaired. How can we figure out ways to still introduce visual learning for these students? How can technology facilitate this type of creativity?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.