As I go through my embroidery free inquiry project, I come to see the myriad ways in which the inquiry itself is not only free but I am freed by it.

There are some very literal, immediate ways this has already happened. When I stitch, I am freed from my computer, to which I am almost continually tethered these days while I earn a degree online, attempt to be a present partner in a long-distance relationship, and have nowhere else to go. When I stitch, I am freed from the constraints on my visual imagination — I am free to externalize my thoughts and move away from the inside of my own head. When I stitch, I am free to relax, freed from the confines of doing something for a specific purpose outside myself (i.e. homework).

But there are broader, more abstract, personal and social ways in which embroidery, and the act of pursuing it freely with no end product to be evaluated, frees me.

De-Commodifying our Hobbies

For another course, my presentation partner and myself are doing a teaching presentation on the anti-oppressive possibilities of using or teaching textiles as an anti-oppressive medium across the curriculum. as it turns out, embroidery, and the act of crafting in general, can be extremely freeing and anti-oppressive.

For me, embroidering means having a hobby that I can enjoy without the constant capitalistic pressure to commodify or monetize absolutely every activity I engage in. I have commodified and capitalized a hobby before with terrible results.

I was a professional baker for a couple of years, and that experience was, for me (not for everyone!) extremely oppressive. A combination of a lack of creative control or exploration, having to be on a particular schedule, and a host of pretty exploitative and, quite frankly, kind of uncaring bosses kind of ruined my hobby for me. One job led me to have really, really severe panic attacks and depression while also leaving my physical body in disarray and leaving me little to no time to engage in my hobby in my own time (I also got fired for essentially telling my boss that these things were going on and that I needed a change in my schedule). Another set of bosses did nothing to communicate with me or accommodate when I broke my finger — an injury which automatically changes your ability to perform your job functions when you work with both of your hands all day. And for all of this, I was paid minimum wage or every-so-slightly above. Capitalism pressured me to commodify something I enjoyed and made it completely unenjoyable while, unsurprisingly, exploiting my labour.

Since leaving that industry, I have been able to take back my hobby. When I have sold baked goods, it has usually been for friends-of-friends who give me full creative control over what I’m doing. This summer, I also chose to use my de-monetized hobby for broader anti-oppressive purposes. I spent my summer this year baking for anti-racist organizations. I took individual, fully custom orders and asked that the buyers cover my ingredient costs and make a minimum donation which would be donated to an anti-racist organization of their or my choosing. I raised over $800 for these organizations, and this was more enjoyable and more meaningful than earning whatever I did in two years as a baker. Many of the things I sold for this also happened to be commissioned by my friends, which meant that I got to partake in the consumption of what they ordered, sharing a pleasurable sensory experience with them. Being able to have time and energy to bake for my friends is one of the most crucial aspects that makes it freeing, positive, and anti-oppressive for me — baking is a way I can connect with and demonstrate my affection for my friends. This has always been more important than nameless strangers giving me their money.

Here are just a few of the things I made for that bake-sale:

The sweet taste of anti-racism!

I have a friend who sews and she makes really cool, handmade clothing. She has been asked by many people if she’s ever considered going into the fashion industry/selling clothes. This question is always well-intentioned — essentially people are giving my friend a compliment on the quality of what she makes. She, like me, hates this pressure to commodify something she loves to do. I have seen this pressure put countless times on people I know — young people who are often precariously, un-, and/or under-employed who are told they aren’t allowed to enjoy anything or have true free time because they’re broke and who are told if they do make actual free time and do things they enjoy for no money, it’s their fault they’re broke. Capitalism tries to trick them/us into thinking it’s their/our fault for being broke and into exploiting themselves.

Welcome, then, to the “Hustle Era” — this Slate article does a great job of explaining what it is and how we got here. Its closing line perfectly encapsulates my own experience with going professional on the baking front: “Very few of those who stress bake will end up professional patissiers, but that’s OK. The point should be pleasure, not profit.” This article goes even further in criticizing the pressures of capitalism on hobbies, pointing out that the measurability of the potential capital “worth” of hobby time (her, specifically embroidery!) can also have the effect of further marginalizing people with disabilities. Regardless of ability, that possibility of quantifying anything based on the capitalistic equation of time=money has the potential to severely “reduce the work’s possibilities as practice, as thinking, as containing the possibility of a body over duration” and to “foreclose [its] communicative potential”.

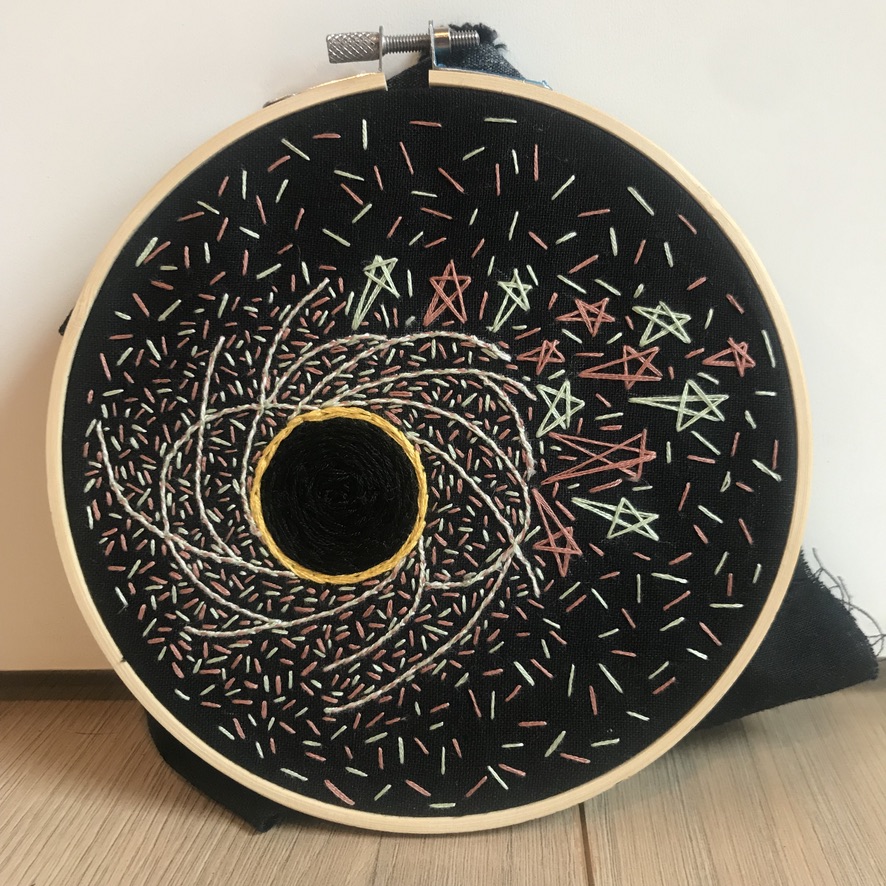

Embroidery, then, allows me to stick it to capitalism in a very small way, as this design attests to:

Instead of falling into the black hole of capitalistic guilt, do what I do — stitch a black hole instead.

Stick it to capitalism — demonetize hobbies! Enjoy free time! Do something just for the heck of it! Learn for the sake of learning!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.